Nature writer Richard Smyth reflects on his long-standing fascination with a bird familiar to the North East’s shorelines

Nothing else looks like a lapwing in flight. It’s not just the striking white underside and the black-bolero wings; nor is it just the extraordinary round-ended wing shape, which makes each wingbeat seem an exaggerated flourish, as if the bird is swimming or elbowing its way through the middle air. There’s something more – something in the character of the lapwing’s flight, something in the lapwing style. Aside from anything else, few other birds seem to enjoy flying as much as the lapwing does.

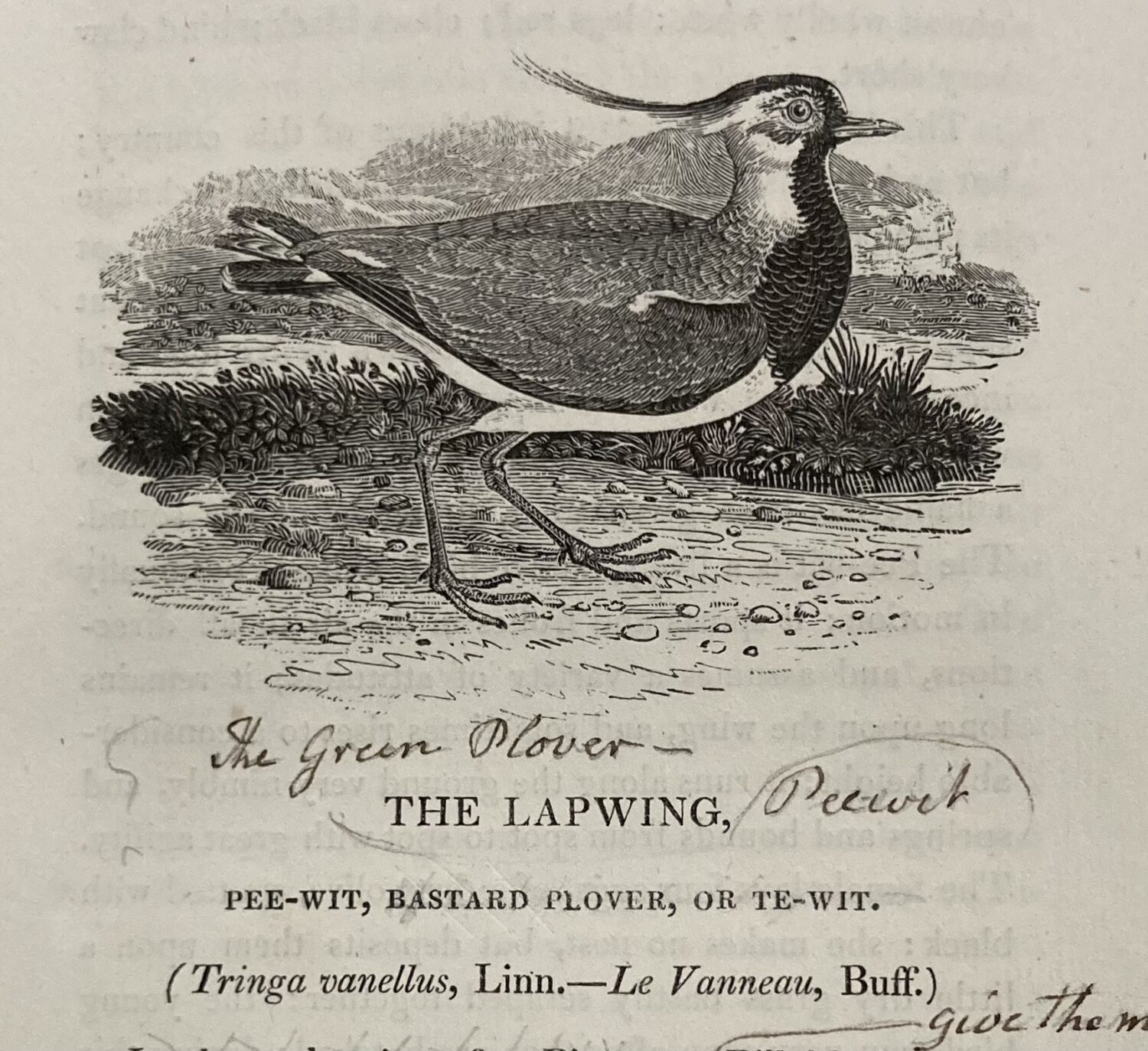

Thomas Bewick, the great Northumbrian engraver and naturalist, described a ‘lively, active bird, almost continually in motion,’ in his History Of British Birds: ‘It sports and frolics in the air in all directions, and assumes a variety of attitudes; it remains long upon the wing, and sometimes rises to a considerable height’. Parties of lapwings in flight always seem to me to be tumbling downward or spiralling up, never just flying somewhere but always making the most of flying somewhere. Then there’s the noises, the extraordinary squeals and whoops and whistles (which earned the lapwing one of its other names, ‘peewit’: it’s a bird known for its wide variety of local sobriquets, which include pyewipe, toppyup, chewit and green plover, though today you seldom hear the name Bewick used, ‘bastard plover’).

Stand on the shore across from St Mary’s Lighthouse at Whitley Bay. Lapwings gather here in their hundreds (along with their close cousins the grey and golden plovers); you can see them waiting on the rocks as the tide musters around their feet, a polite assembly, patient and quiet – until, for reasons of their own, they go up, all at once and all together, and put on an impromptu airshow, and you can watch them waving like a great flag back and forth across the eastern sky.

The spectacular flocking of lapwings has long been celebrated. In the 1950s the Durham naturalist George Temperley wrote of ‘very vast flocks … passing over the Tees Estuary’. But Temperley also wrote of an ‘extraordinary diminution in numbers’ since the 1920s – and this diminution is, sadly, still going on. The lapwing, especially as a breeding bird of lowland farmland, has been in steady decline for decades; the UK breeding population has fallen by about 67% since since the late 60s.

For all that I enjoy the sensory richness and show-offy choreography of lapwings in flock, there’s always been, for me, something special about the lone lapwing. I think of this as a bird of just-dusk and clear skies – leaping up into flight from fields beside an A-road, typically, wings working, spiralling like a launching rocket gone off-course, and somehow filling the empty petrol-blue with just itself, just its own kinetic clarity and strength and sense of being sharply alive.

The poet Edward Thomas memorably described pair of lapwings in flight ‘under the after-sunset sky’: ‘More white than is the moon on high/Riding the dark surge silently; More black than earth.’

As population declines continue, the lone lapwing takes on another, more lonely aspect. It may soon become a rare thing to see lapwings in great number at all – we may have to get used to a world in which the lapwing has not only declined, on our farmland, our heaths and moors, our coasts, but has left us altogether.