In the fourth instalment of her series on the citizen scientists of the late nineteenth-century Northumbrian coalfield, Maureen Flisher follows ‘Miner Swain’, a miner whose identity can only partly be traced, but who both discovered a dinosaur and took part in a heroic attempted rescue.

As I continued to research the pitmen naturalists of West Cramlington and Newsham, I came across two entries in the NHSN Proceedings of 1889 that fascinated me. In 1870, “Miner Swain” had “observed in the overhanging shale, where he was working, indications of a chain of bones which he rightly took for the remains of some large animal. The object noticed being of unusual magnitude he was anxious and careful to obtain it in as perfect a state as possible. Laying down his rough coat on the floor of the mine under the position of the fossil, and gently detaching the shale in which it was imbedded, he placed it in 8 pieces, on his coat and conveyed the whole ‘out-bye’, thence to Newcastle to Mr Barkas.”

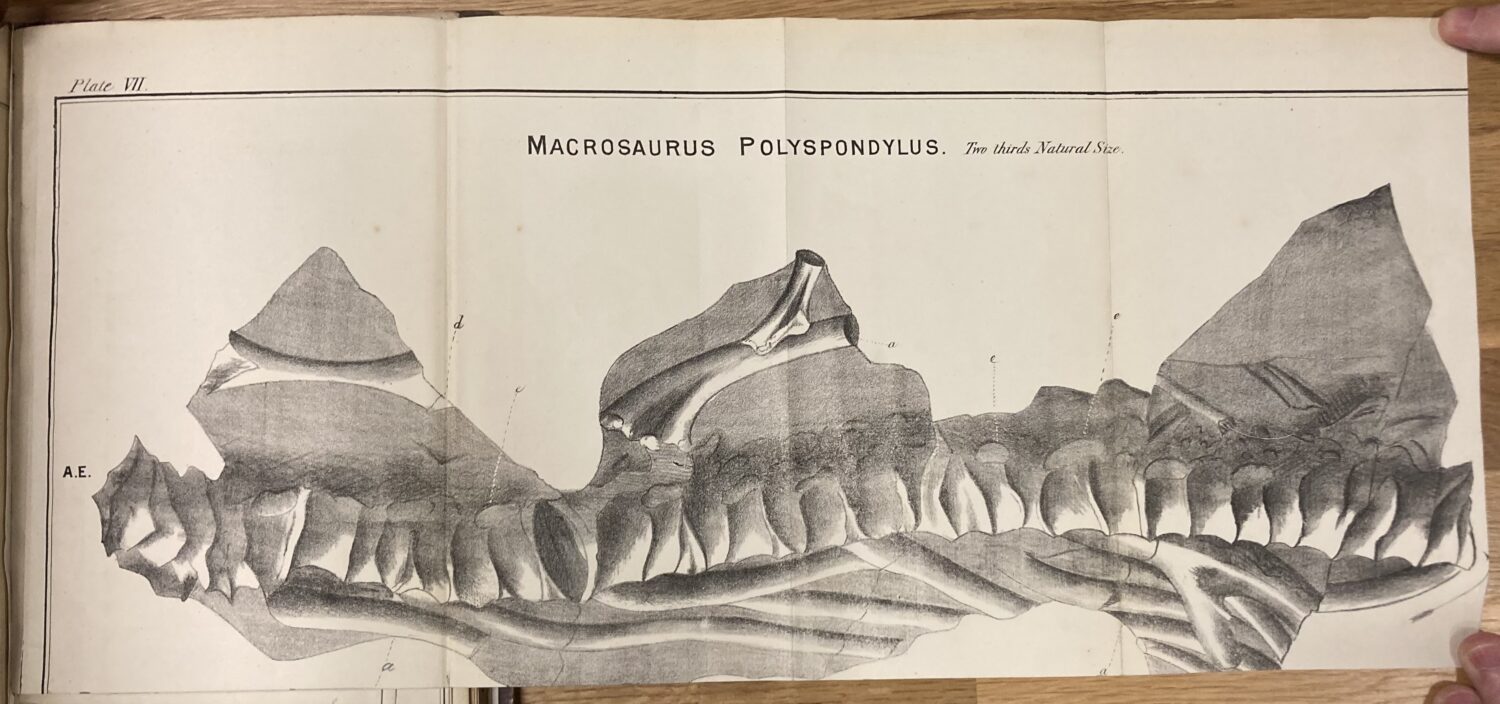

Thomas Pallister Barkas – the paleontologist, educator and scientific gadfly we encountered in previous ‘Pitmen Naturalists’ blogs – believed the object to be a vertebral column, though much obscured by the material it was imbedded in. He carefully worked on a small section of the matrix, removing just as much shale as he dared. In his book A Manual of Coal Measure Palaeontology , published in 1873, he declares that this partial specimen “is the most consecutive series of vertebrae of a Coal Measure Air- Breather to be obtained”. He temporarily named it Macrosaurus polyspondylus.

In 1877, Barkas would place the specimen in the hands of Thomas Atthey (1814-1880), a skilful preparer and investigator of fossils, to be worked on for presentation to the Newcastle Museum. Atthey worked on the shale slabs tirelessly for over a month but sadly suffered a stroke before his work was complete.

In 1889, William Dinning took on the task, “enclosing the shale slabs in an artificial matrix and frame”. He uncovered “a much longer series of vertebra of the spinal column”. A paper presented to the Society’s Council estimated the creature “similar to an adult crocodile or alligator, to be approximately 14 ft in length. …A creature that would have wandered the swamps millions of years ago”, brought into the daylight by a miner who knew that what he had found was significant, and should be preserved for further investigation. This type of vertebrae is now known as Pholiderpeton attheyi.

What of Miner Swain? Was he feted for the effort he had gone to, and how had he travelled to Newcastle with sections of shale measuring over “56 inches in length”, wrapped in a coat? I cannot answer that as I can find no other record of a “Miner Swain” in any of NHSN’s records or in Barkas’ book.

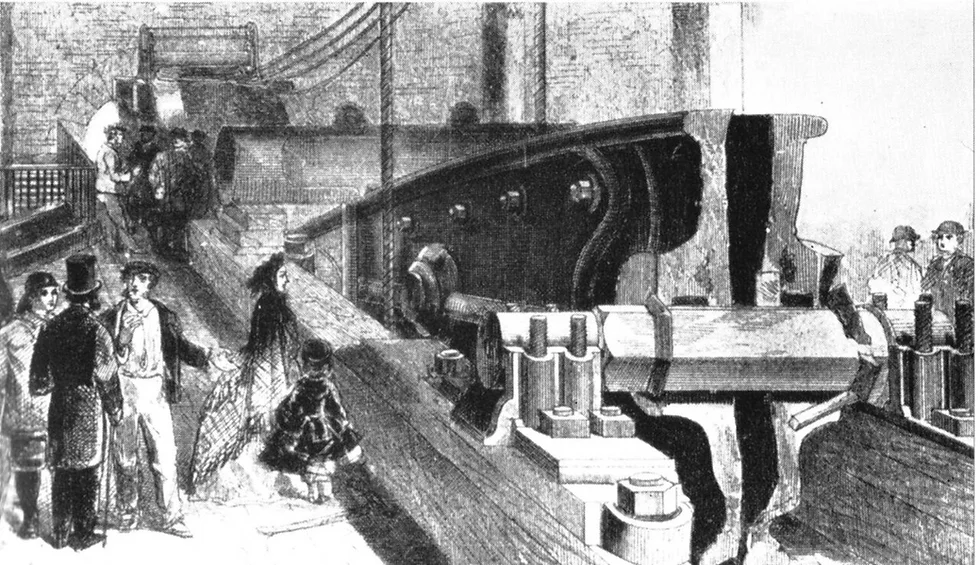

Census records suggest that Miner Swain was actually Andrew Swain, born in 1827, or his brother William born in 1834. They both worked as miners, but as Andrew was living in Newsham in 1861, it seems more likely that he is “Miner Swain”. He is one of the brave men who, during the Hartley Pit Disaster of 1862, volunteered for the dangerous task of descending into the blocked shaft, attempting to clear it in order to save the lives of 204 men and boys trapped below. The rescuers were unable to save the lives of the victims – one of the worst disasters in British mining history – but Swain and other “sinkers” were later presented with commemorative medals for their bravery. An extraordinary individual, in more ways than one.

The author wishes to thank:

Sylvia Humphrey, Assistant Keeper of Geology at Great North Museum: Hancock, for patiently answering the many queries I posed regarding the GNM – Hancock collection of Coal Measure Fossils.

Jim Fagan, for further newspaper and genealogy research.